A Brief Introduction to Corpora and the Lingonet Video Corpus

Dr Mike Nelson

1. Corpora: what are they and where did

they come from?

What is a corpus ?

The term

corpus

(plural corpora) comes from the Latin word meaning

body. Thus, in the case of language, we are talking about a body

of language - a collection, usually computer-stored, of language which can then

be used for analysis.

How did corpora begin and develop ?

Corpus linguistics - using corpora to study language, has had a

somewhat chequered history in the world of language research. Its origins can be

traced back mainly to the 19th century (though analysis of Shakespearean texts

was undertaken already 400 years ago) and the image of silver-haired

professors straining over mountains of text and manually counting occurrences of

linguistic features, has been a hard one to dispel. Have a look here for more

information about the history of corpora.

http://www.ling.lancs.ac.uk/monkey/ihe/linguistics/corpus1/1fra1.htm

The field was, however, held in some regard until an

infamous attack on its basic premises by Chomsky.

In a number of articles in the late 1950s and

1960s, Chomsky challenged the whole notion of empiricism on which corpus

linguistics was based and suggested instead a rationalist approach. As Chomsky

was more interested in competence than performance, corpus linguistics, which

was primarily based on actual performance seemed to be invalidated overnight. It

led to a situation that Sinclair describes:

Starved of adequate data, linguistics languished - indeed

it became almost totally introverted. It became fashionable to look inwards to

the mind rather than outwards to society. Intuition was the key, and the

similarity of language structure to various formal models was emphasized.

Sinclair (1991:3)

Work on corpora continued despite these criticisms and, with the

advent of the computer, really came into their own. The work begun in the early

sixties by Randolph Quirk (the SEU Corpus), and Francis and Kucera (The Brown

Corpus) was capitalised on by Svartvik in creating the London-Lund Corpus (LLC),

creating a machine readable corpus of spoken language for the first time. By the

1980s corpus linguistics had almost found its way back into mainstream applied

linguistics. This rise of corpus-based research can be seen in the number of

corpora created. Svartvik (1992:8) shows that only ten were created before 1965,

but between 1986 and 1992, 320 have been created. It is safe to say that

most recent work on the large scale has been concerned with dictionary creation,

and as teachers we are all aware of, for example, the COBUILD project, and

perhaps also the British National Corpus (BNC) which has been developed by

Oxford University Press, Longman and Chambers. Corpora are back in

vogue.

2. Key terminology

In this section

we will look at two of the key concepts used with corpora.

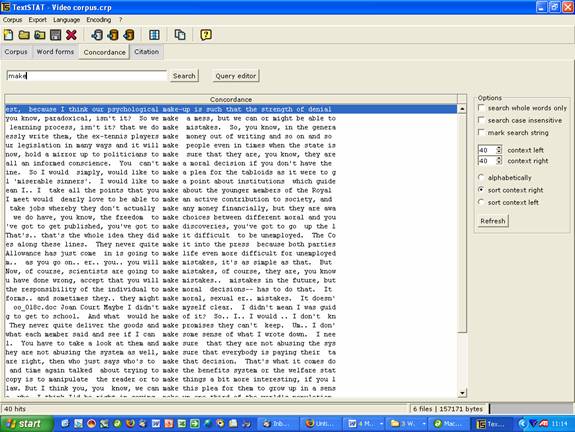

2.1 Concordancing

Concordancing is the act

of picking out examples of a given word in context. The software used for doing

this are often called KWIC concordancers (Key Words In Context). Thus, for

example if we are interested in the word “dog” the concordancing program would

search out all examples of the word and place them in rows with the word “dog”

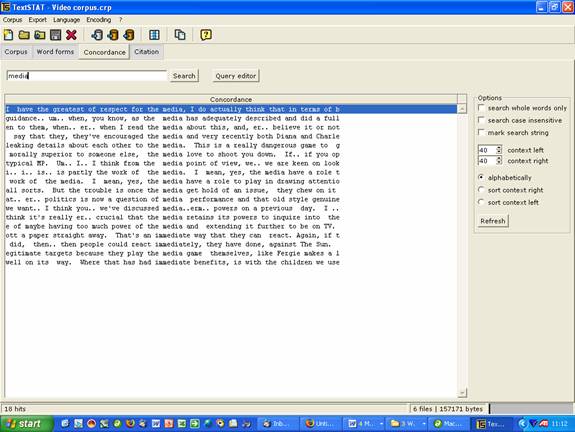

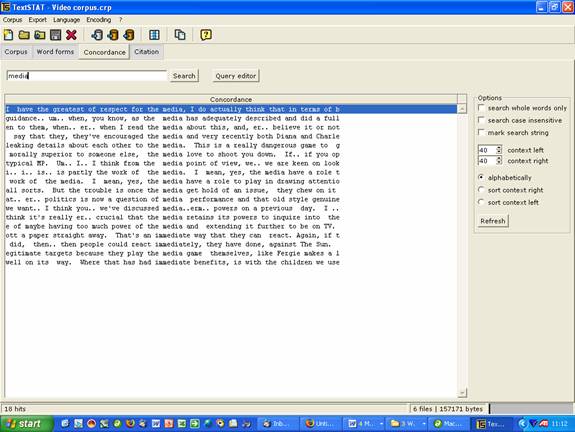

in the middle. Have a look below to give you some idea of what a concordance

line looks like, using the word ‘media’ taken from the Video Corpus.

2.2 Collocation

There are many definitions

for what collocation is, but basically it refers to how words co-occur. Thus the

word blonde co-occurs almost always with the word hair. They

are thus said to collocate. Collocations can be strong e.g. vested

interest or weak e.g. brown hair. For more on this look now at these

collocations taken from a business English corpus of words that collocate with

the word market.

stock market, market share, single market, mass

market

market leader, market driven, market segment

In order to do concordancing, first of all you need both a

corpus, a computer and some kind of software to run it. There are several

commercial packages available for looking at corpora and concordancing, but this

package uses TextSTAT:

http://www.niederlandistik.fu-berlin.de/textstat/software-en.html

3. Using Corpora : in research and in the

classroom

Murison-Bowie (1996:182) in an article entitled

Linguistic Corpora and Language Teaching notes that over the last

few years there have been two opposing views of using corpora in research and

language teaching:

The Strong View says that without a

relevant corpus no meaningful work can be done.

The Weak

View states that corpora give us a valuable insight into language and

how it works and this is something we can draw on in our teaching.

Which side do you come down on? Perhaps the safest way is to stick to the weaker side. For example, much corpus work hinges on the concept of frequency. The theory goes that the more frequent a word is, the more important it is to teach it to students. However, the most frequent word in English is “the” and whilst it is no doubt important to make sure our students can master the article system , it doesn’t get them very far in other ways. Remember the complaints of Chomsky discussed earlier? He dismissed frequency by saying it was of no importance at all and he gave this example:

“I live in Dayton, Ohio.”

“I live in New York”

In the English language the first sentence will always be

less frequent than the second, thus the data in any corpus would be naturally

skewed and therefore useless. Michael Lewis in his talk at the 1998 IATEFL

conference when launching LTP’s new collocational dictionary suggested a

sensible middle-ground. Use a corpus - but also use your common sense and

intuition. Corpora can and have been used to give us great insights into the

language. What follows are a few examples I have come across in my own

research.

Research

Holmes (1988) made a study of how the concepts of doubt and certainty are presented in ESL textbooks. She, herself, advocated the use of small corpora and used a combination of two corpora to compare findings to an examination of four well known textbooks. Her results showed that whilst in some cases, doubt and certainty - were adequately covered, “some textbooks were positively misleading” (Holmes 1988:40). She noted that other books give information of “variable quality” (1988:40). Interestingly, she also dismisses earlier attempts of analysis of this issue on the grounds that the research had not been corpus based, but along rationalist lines.

In another study, Kennedy (1987) looked at quantification, more

specifically the use of approximation, and how it is used by native speakers.

Two corpora and the Oxford Concise Dictionary were consulted and compared to

input from teachers who were asked to give their own intuitive input on the

subject. The results showed that the intuition of the teachers gave the largest

range of types of approximation terms, but that on its own it was not enough.

The vast amount of intuitive information needed ordering and:

the frequency data which the computer-based examination of

these types in large corpora now makes possible were also necessary to give the

descriptive information pedagogical value.

Kennedy (1987:282)

Flowerdew (1991) compared biology lecture notes to the COBUILD corpus and to published material and found several differences, for example, the use of the word then.

Ma, (1993) studied the difference between a corpus of 50 business letters and published materials for its teaching and also noted several differences, for example, use of the PS section of letters was not covered in the materials, but widely used in real life.

Pickard (1992) noted that the language of refutation used in textbooks was not actually used in real life.

Ljung (1990), in “A Study of TEFL Vocabulary” created a corpus of TEFL textbooks used in Swedish schools and compared it to several corpora, notably COBUILD. He found great discrepancies between “real” vocabulary and the materials used for teaching it. A frequency count showed that 204 words out of the top 1,000 were not shared by the two corpora showing a significant difference in emphasis, especially between concentration on concrete terms in the EFL corpus to more abstract terms in COBUILD. In his conclusion, he notes that:

there is reason to be critical of the TEFL texts on two major

counts, i.e. the low general level of lexical sophistication and the absence of

a clear increase in vocabulary difficulty as we move from the early to the later

school years.

Ljung (1990:44-45)

He goes on to note that the materials do not adequately prepare

the students for the tasks of the real world.

Thus, it can be seen

from these studies that corpus-based examination can be a very useful exercise.

In each of the examples we find that the text books to some extent had got it

wrong. Thus if text books are all flawed what should we do ? This leads us very

nicely to the next section where we can look at actual corpora and see what we

can do with them in the classroom.

4. The

Classroom

So what can you do in the classroom with a

corpus? There are several things that can be done very easily:

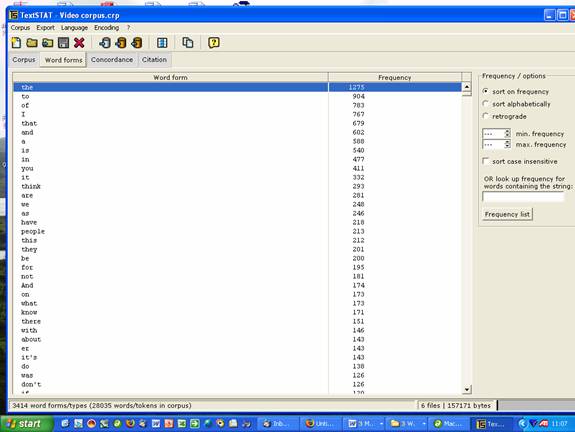

4.1 Looking at Frequency This is the most simple and most corpus analysis tools will give you the frequency lists of texts. This is perhaps not very interesting, but it can show - apart from all the grammar and function words - which special words, for example, in a given genre are the most frequent. Thus you could feed in the language found in this Video Corpus and compare it to a general English corpus.

Here we see the frequency list of the Video Corpus:

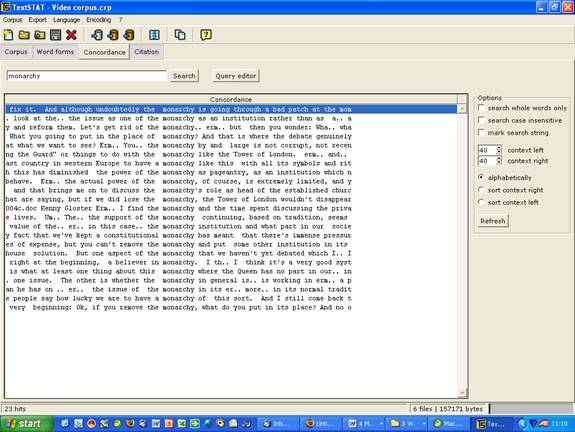

4.2 Looking at Collocations The fact that computers can generate such a large amount of collocations in seconds affords the teacher and student access to very interesting and relevant information. For example, a business English student wants to know more about how the word market is used. The word can be keyed in and the collocates examined. In this way new collocates and even idiomatic phrases can be seen in context and learned. Have a look at Michael Lewis’s book Implementing the Lexical Approach for a much more detailed account of how this can be done.

Here we can see collocates of the word 'monarchy' taken from the Video Corpus.

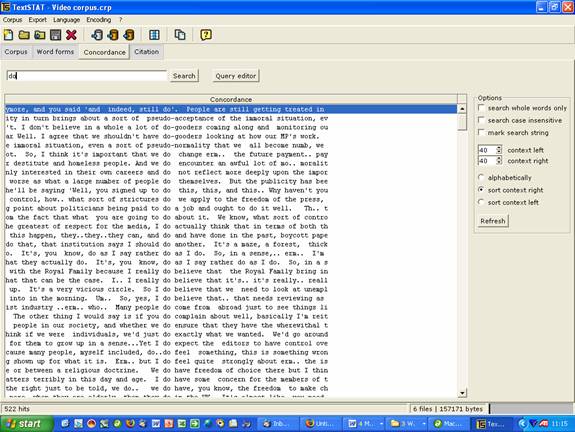

4.3 Looking at Words in context: Concordance

lines can give you not only the words immediately around a key word but you can

also see the word or form you are looking at in larger context.

4.4 Looking at Test design - using gap-fill

corpus-based

Butler, 1991, used a concordancer to help design

tests. He searched out key words in context using a corpus and the test process

then became one of choice for the teacher - choosing from items presented -

rather than just sitting down and thinking what would be good examples to test

the items.

4.5 Getting students to see grammatical patterns:

For more advanced students you can use a corpus for them to

see how certain grammatical patterns are used in real speech/writing. In 1988,

Johns use a corpus to get his students to look at the differences when the word

“to” is used as an infinitive and when it is used as a preposition. He also

asked them to look at how the words “therefore” and “hence” differentiated in

their use.

Why not try stating with something very simple, e.g. examining the difference between “make” and “do” by looking at which words collocate with them.

Concordance line of 'make' taken from the Video Corpus:

Concordance line of 'do' taken from the Video Corpus:

5. Exercise types you can easily

develop from the Video Corpus

This next section will show you a few exercise types that are

very easy to make once you have a corpus to work from.

5.1 Working with collocates -

before or after the keyword ?

In this kind of exercise you can use a

corpus to generate collocates of given key word. Then, mix them up and ask the

students to decide if the words come before or after the key word. This helps

with familiarity and meaning can be discussed in the lesson.

5.2 Fill in the gaps

The old standard

gap-fill type exercises are much better when you can take them directly from an

authentic corpus - just remove collocates or key words and get the

students to fill them back in again.

5.3 Linking

sentences

Again, another very simple old

exercise. Take sentences from the corpus and split the sentences in half. Then

ask the students to put them back together again.

6. Beyond the silent corpus

The big advantage that is to be gained from using the Video Corpus is the fact that the text 'comes to life' and all the texts that are available for concordancing and analysis can be watched and listened to in the precise manner in which the language was originally used. The sound and vision also offer new possibilities for the classroom.

6.1 Listening for linguistic devices

The possibility for listening can help in exercises based around certain linguistic devices, for example, hesitating devices found in the text below. Further use of fillers and false starts can also be analysed.

Right. Um.. Yes, of course, I do think we

need a welfare state um.. in order to

accommodate the needs

of the weaker members of our society. It's absolutely

essential.

Um.. And Britain was really at the forefront in.. in

setting up its welfare

state in the middle of the century.

Um.. And I think that's something we should be

very proud

of. What is rather sad I think is that a lot of people are now feeling as

though they've been conned, um.. particularly elderly

people who have erm.. paid their

national insurance stamps

for many many years, expecting to be cared for, in their,

when they become older.

6.2 Video for discussion

As the students are able to see and listen to all the texts in the corpus they can be used as preparatory material for group discussions. Individual students can separately watch the opinions given by different members of the panel and then elaborate on their arguments for their own debates on the issues as part of group discussions.

6.3 Video for presentations

In the same manner, students can use the information gained from the corpus and the opinions given to prepare their own presentations on the same topics.

6.4 Video for pronunciation, word stress and inflection

The texts in their audio-visual form can be used to study the pronunciation of words and the word stress and inflections used.

6.5 Video for body language

The video can be used for the study of body language in relation to speech: is there specific body language attached to certain words/ideas?

7. Conclusions

In this short article we have seen that

despite the arguments against corpora, it can be argued that they are an

effective method for both research and for organising exercises for the

classroom. The argument over the sufficiency of the concept of frequency over

the intuition of native speakers will continue to rage. The middle ground,

however, can be taken - use a corpus to get the data and then use your

intuition on how to get the best out of it.

Gathering, collecting and

organising a corpus of your own is a time consuming and often boring process.

The Video Corpus provides you with a small but useful body of language to

utilise in the classroom. You can thus have instant access to authentic,

relevant and hopefully motivating language.

8. Background reading

There is a marvellous full on-line course on corpus linguistics at Lancaster University http://www.ling.lancs.ac.uk/monkey/ihe/linguistics/contents.htmcreated by Tony McEnery and Andrew Wilson. Please have a look through- even if you don’t want to do it all.

Note that they have a full section on Corpora in language teaching at: http://www.ling.lancs.ac.uk/monkey/ihe/linguistics/corpus4/4fra1.htm

See David Lee's great site on everything related to corpora Devoted to Corpora

and Bibliography

Butler, J. (1991) Cloze procedures and concordances:

the advantages of discourse level authenticity in testing expectancy

grammar in System 19 (1/2), 29-38

Flowerdew, J. (1991)

Corpus-Based Course Design in Milton, J.C. and Tong, K. (eds) Text Analysis

in Computer Assisted Language Learning, 31-43. Hong Kong: The Hong Kong

University of Science and Technology and the City Polytechnic of Hong

Kong

Johns, T. (1988) Whence and Whither Classroom

Concordancing ? in Bongaerts, T. et al. (eds) Computer Applications in

Language Learning. Dordrecht: Foris

Kennedy, G, D.

(1987) Quantification and Use of English: A Case Study of One Aspect of

the Learner’s Task in Applied Linguistics Vol 8 No. 3 Oxford: Oxford

University Press

Lewis, M. (1993) The Lexical

Approach Hove: LTP

Ljung, M. (1990) A Study of TEFL

Vocabulary Almqvist and Wiksell International: Stockholm,

Sweden

Ma, K.C. (1993) Text Analysis of Direct Mail Sales

Letters in Boswood, T., Hoffman, R. and Tung, P (eds) Perspectives on English

for Professional Communication Hong Kong: City Polytechnic of Hong

Kong

McEnery, T. and Wilson, A. (1996) Corpus Linguistics

Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

Murison-Bowie, S.

(1996) Linguistic Corpora and Language Teaching in Annual Review

of Applied Linguistics 16, 182-99: Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press

Pickard, V. (1991) Should We Be teaching Refutation ?

Concordanced Evidence From the Field of Applied Linguistics Paper

presented at the Eighth ILE International Conference 15-18 December,

1992

Sinclair, J. (1991) Corpus, Concordance, Collocation

Oxford: Oxford University Press